Copernicus – A True Renaissance Man

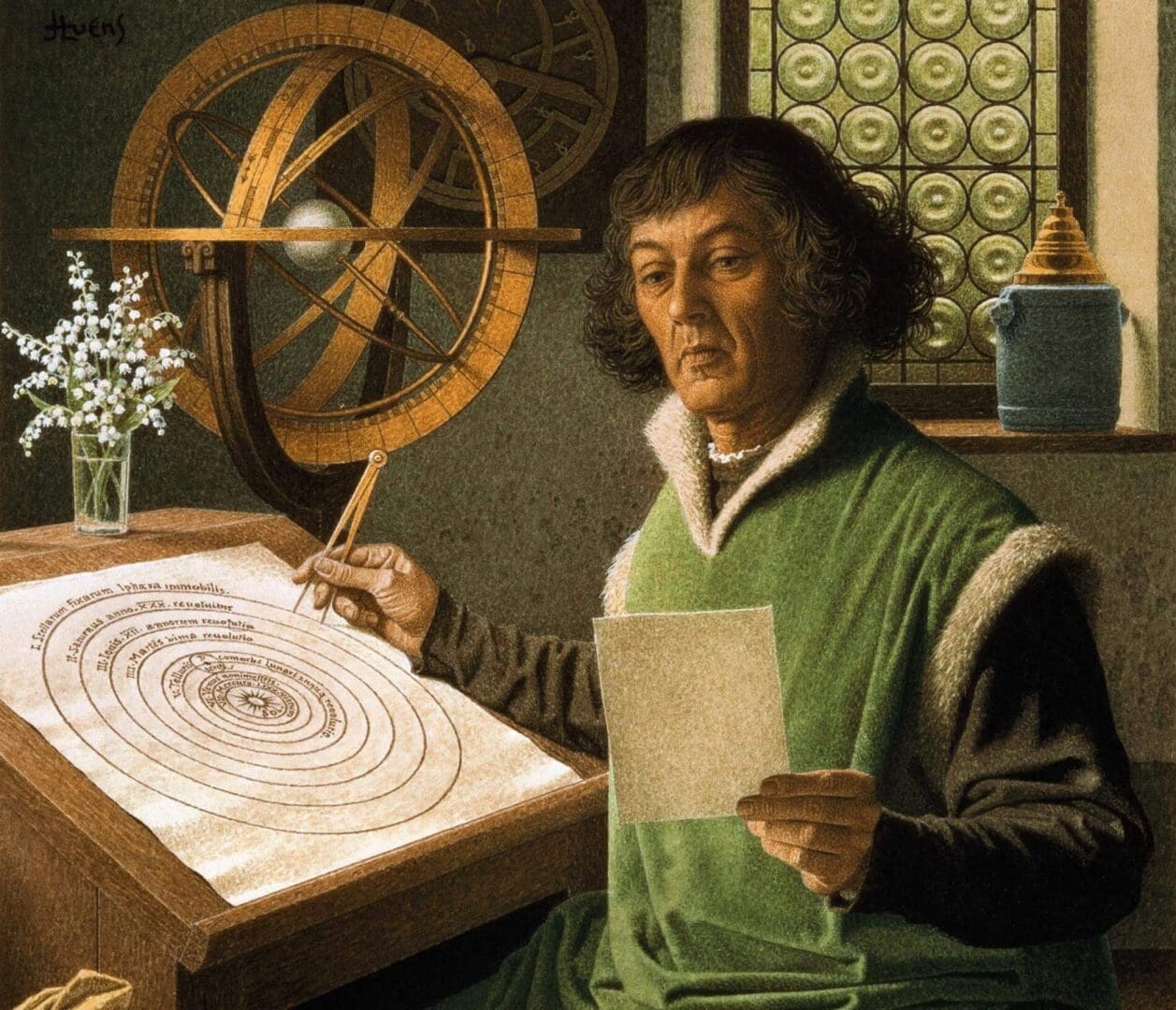

MikoÅ‚aj Kopernik (1473 – 1543) was a Renaissance-era astronomer who can accurately be described as a true Renaissance man. First coined in the early 20th century, the expression describes a well-educated person who excels in a wide variety of fields. Fulfilling this ideal, Copernicus was a mathematician, astronomer, church jurist with a doctorate in law, physician, translator, artist, Catholic cleric, diplomat, and economist. He spoke German, Polish, Latin, Greek, and Italian. The vast majority of Copernicus’s surviving works are in Latin, which in his lifetime was the language of academia in Europe. MikoÅ‚aj is Polish for Nicolaus and Copernicus is the Latinization of his surname Kopernik.) He is undoubtedly one of the most important astronomers of all time and was the first to provide proof that the Sun, rather than the Earth, was at the center of the Solar System, which many scientists regard as the beginning of our increased scientific understanding of the universe.

Born in Toruń (famous for its gingerbread), he was the youngest of four siblings in a well-to-do family. His father, Nicolaus, was a merchant from Kraków and his mother, Barbara Watzenrode, was the daughter of a wealthy Toruń merchant. His father died when he was 10 as did his mother at about the same time. His maternal uncle, Lucas Watzenrode, was a wealthy, powerful man who adopted Nicolaus and his siblings and secured the future for each of them.

Copernicus first enrolled in the Kraków Academy and studied astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, and natural sciences. He then went to the University of Bologna and studied law. This part of his education is said to have perfected his logical thinking abilities, a skill crucial to the later development of his heliocentric theory. He then studied medicine in Padua and got a doctorate in law at the university in Ferrara. With the doctorate in law, he obtained a lucrative position in the Diocese of Warmia (in Poland) and this secured a lifetime’s livelihood that gave him the money he needed to further develop his intellect. While we may know him as an astronomer, his contemporaries knew him as a physician. He was considered a skilled practitioner of medicine, which, at a time when there were very few doctors, was enough to make you famous.

Copernicus for years advised the Warmia parliament on monetary reform, particularly in the 1520s when that was a major question in regional politics. In 1526 he wrote a study in which he formulated a theory on the value of money, now called Gresham’s law, which preceded Thomas Gresham by several decades. In 1517, he also set down a quantity theory of money, a main concept in economics to the present day. Copernicus’s recommendations on monetary reform were widely read by leaders of both Prussia and Poland in their attempts to stabilize their currencies.

For relaxation, Copernicus painted and translated Greek poetry into Latin. His interest in astronomy gradually grew to be one in which he had a primary interest. His investigations were carried on quietly and alone, without help or consultation. He made his celestial observations from a turret situated on the protective wall around the cathedral in Frombork (in northern Poland). His observations were made “bare eyeball”, so to speak, as a hundred more years were to pass before the invention of the telescope.

He then developed his heliocentric theory, which was supported by a range of mathematical calculations. His theory stated the following: 1) Planets don’t revolve around one fixed point 2) The Earth is not at the center of the universe 3) The sun is at the center of the universe, and all celestial bodies rotate around it 4) The distance between the Earth and Sun is only a tiny fraction of stars’ distance from the Earth and Sun 5) Stars do not move, and if they appear to, it is only because the Earth itself is moving 6) Earth moves in an orbit around the Sun, causing the Sun’s perceived yearly movement 7) Earth’s own movement causes other planets to appear to move in an opposite direction.

Copernicus’s theories incensed the Roman Catholic Church and were considered heretical. When his theories were published in 1543, religious leader Martin Luther voiced his opposition. Two other Italian scientists of the time, Galileo and Bruno, embraced the Copernican theories unreservedly and as a result suffered at the hands of the powerful church inquisitors. For such blasphemy, Bruno was tried before the Inquisition, condemned, and burned at the stake in 1600. Galileo was brought forward in 1633, and under the threat of torture and death, was forced to his knees to renounce all belief in Copernican theories, and was thereafter sentenced to imprisonment for the remainder of his days. Some people, among whom John Donne and William Shakespeare were the most influential, feared Copernicus’s theories, feeling that they destroyed hierarchal natural order, which would in turn destroy social order and bring about chaos.

Copernicus’s theories had important consequences for later thinkers of the scientific revolution, including major figures such as Galileo, Kepler, Descartes, and Newton. Scholars did not generally accept the heliocentric view until Isaac Newton, in 1687, formulated the Law of Universal Gravitation. This law explained how gravity would cause the planets to orbit the much more massive Sun and why the small moons around Jupiter and Earth orbited their home planets.