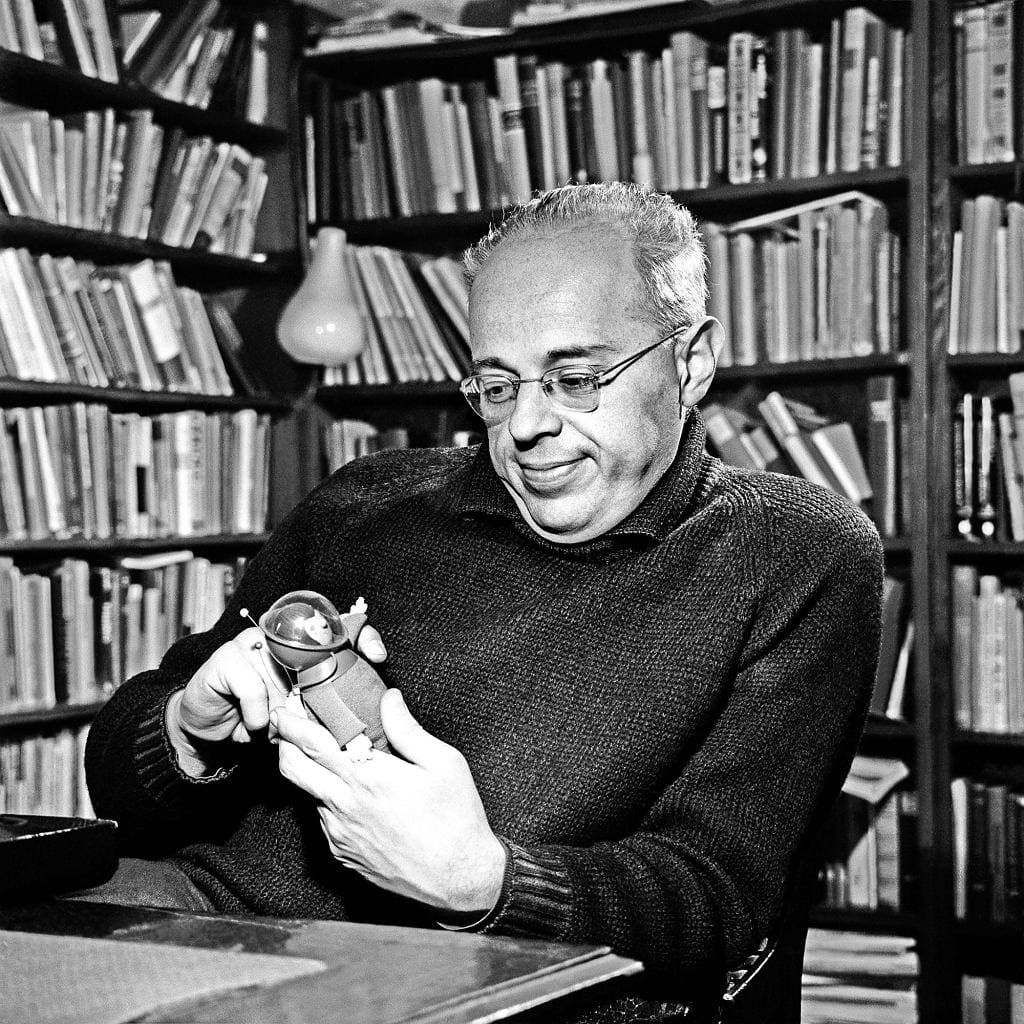

Stanisław Lem: The world’s most widely read science fiction writer

Stanislaw Lem’s books have been translated into more than 50 languages and have sold more than 45 million copies. Worldwide, he is best known as the author of the 1961 novel Solaris. Throughout a career that spanned six decades, Lem produced more translated works than any other Polish writer. His bibliography includes 18 novels, 14 anthologies of short fiction, and 14 nonfiction works that encompass “hard science-fiction”, which is evident by his adherence to scientific accuracy. In addition, many of his works are satirical and humorous.

Stanislaw Lem (1921-2006)

Describing himself as a futurologist, Lem foresaw technological capabilities that we today take for granted. He envisioned maps that could plot a route at a touch, immersive artificial realities, and instant, universal access to knowledge via “an enormous invisible web that encircles the world.” When he toured the Soviet Union in the 1960s, he addressed standing-room-only crowds and was greeted by astrophysicists and cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin.

Behind the Iron Curtain in the 1950s, Lem constructed his own brand of science fiction that was different from what was popular in the United States. He paid close attention to the scientific discoveries and theories of his times and focused on space travel, chemistry, genetic engineering, and mathematics. In recognition of this, a Polish optical astronomy satellite named Lem was launched in 2013 as part of the Bright-star Target Explorer (BRITE) program. Also in 2013, two planetoids were named after Lem’s literary characters. The first is 343000 Ijontichy, after Ijon Tichy, and the second is 343444Halluzinelle, after Tichy’s holographic companion Analoge Halluzinelle from the German TV series “Ijon Tichy: Space Pilot”. His popularity in Poland also remains strong as evidenced by 100,000 of his books sold annually in Poland and by the Polish Parliament’s declaration of 2021 as the Stanislaw Lem Year.

Lem was born in 1921 to a Jewish family in Lwow (Lviv in today’s Ukraine). His father was an affluent laryngologist and former physician in the Austro-Hungarian Army. After the Soviets invaded and occupied the eastern half of Poland in 1939, they would not allow him to study at Lwow Polytechnic because of his “bourgeois origin”. However, because of his father’s connections, Lem was accepted to study medicine at Lwow University in 1940. During the same time, the Soviets deported and later secretly executed many of Lwow’s defenders, and, in the following months, the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, arrested thousands of the city’s Polish elite. Historians estimate that, while the Soviets were occupying eastern Poland, they deported up to a million and a half Polish citizens. An NKVD officer was boarded in the Lem family home, and whenever they noticed him hard at work, they warned friends to hide.

Hitler then attacked the Soviet Union in 1941 and brutally occupied the region until 1944. As the Germans closed in, the NKVD deported about a thousand prisoners and then, in a panic, executed thousands more. The Lem family’s NKVD boarder, in his haste to depart, left behind pages of handwritten poetry, while in Lwow’s prisons, the boarder’s Russian comrades left behind decomposing corpses. The Germans now saw a propaganda opportunity and blamed the Soviet killings on Lwow’s Jews. The Germans then recruited, encouraged, and supervised a militia of Ukrainian nationalists who carried out a three-day pogrom, which was witnessed by Lem. His family was able to avoid imprisonment in the Lwow Ghetto that the Germans established for Jews. While Lwów was under German occupation, Lem was able to obtain false identity papers identifying him as Jan Donabidowicz and he worked as a car mechanic in a German company established in the city for wartime production. He also occasionally stole munitions from the company’s storehouses so they could be passed to the Polish resistance.

After the war ended in 1945, Lwow was annexed into the Soviet Ukraine, and the family, along with many other Polish citizens, resettled to Krakow, where Lem began medical studies at the Jagiellonian University. He did not take his final examinations on purpose, purportedly to avoid the career of a military doctor. However, the likely reason was that he would have been assigned to a hospital subordinated to the infamous UB (Urzad Bezpieczenstwa), the Secret Police of the Soviet-backed communist government, officially called the Polish Ministry of Public Security. The UB was created to arrest, torture, and murder Poles known or suspected of resisting the new communist government and it was well-known that UB doctors were used to “restore the conditions” of those tortured during interrogation.

Lem started his literary work in 1946 with a number of publications in different genres, including his first science fiction novel, The Man from Mars (Czlowiek z Marsa). During the era of Stalinism in Poland, which had begun in the late 1940s, all published works had to be directly approved by the communist state. In 1951, he published his first book, The Astronauts (Astronauci). Soon thereafter, he met Barbara Lesniak, a medical student nine years his junior, and they married in 1954. Lem became truly productive after 1956, when Poland experienced an increase in freedom of speech following Stalin’s death and the de-Stalinization period in the Soviet Union. Between 1956 and 1968, Lem authored seventeen books and his writing over the ensuing three decades was split between science fiction and essays about science and culture.

Tomasz Lem, the writer’s son said: “It seems that chronologically speaking there were a least three Lems. The very young one wrote science or even pulp fiction, the middle-aged one wrote fiction about science, while the mature one abandoned fiction and turned to philosophical essays.” A review of some of Lem’s works translated to English confirms this, as well as his brilliance as a futurologist and intellectual.

The Cyberiad (Polish: Cyberiada) is a series of humorous science fiction short stories and the main protagonists of the series are Trurl and Klapaucius. Trurl and Klapaucius are “wizard robots” – brilliant engineers, also called “constructors” because they can construct practically anything at will – and are capable of almost God-like exploits. For instance, on one occasion Trurl creates an entity capable of extracting accurate information from the random motion of gas particles, which he calls a “Demon of the Second Kind”. On another, the two constructors rearrange stars near their home planet in order to advertise. The duo are best friends and rivals. When they are not busy constructing revolutionary mechanisms at home, they travel the universe, aiding those in need. As the characters are firmly established as good and righteous, they take no shame in accepting handsome rewards for their services. If rewards were promised and not delivered, the constructors may even severely punish those who deceived them. The vast majority of characters in the stories are either robots or intelligent machines, and the stories focus on problems of the individual and society, as well as on the vain search for human happiness through technological means.

Polish book cover for Lem’s “The Cyberiad,” by graphic artist Daniel Mróz

Solaris, one of Lem’s best-known works, follows a crew of scientists on a research station as they attempt to understand an extraterrestrial intelligence, which takes the form of a vast ocean on the alien planet called Solaris. Solaris chronicles the ultimate futility of attempted communications with the extraterrestrial life inhabiting the planet, which is almost completely covered with an ocean of gel that is revealed to be a single, planet-encompassing entity. The scientists assume that it is a living and sentient being, and they attempt to communicate with it. Shortly before the chief scientist arrives, the crew subjects the ocean to an unauthorized experiment with a high-energy X-ray bombardment. This gives unexpected results and becomes psychologically traumatic for them as they realize they are flawed humans. All of their human efforts to make sense of Solaris’s activities prove futile. Prominent film adaptations of Solaris include Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 version and Steven Soderbergh’s 2002 version, although Lem later remarked that the film did not reflect the book’s thematic emphasis on the limitations of human rationality.

One of many editions of Lem’s book Solaris

Summa Technologiae, Latin for “Compendium of Technology”, is one of the first collections of philosophical essays by Lem. The book exhibits depth of insight and irony, which are typical of Lem’s works. The name alludes to Summa Theologiae, “Compendium of Theology”, by Thomas Aquinas. The primary question Lem addresses is that of civilization in the absence of both technological and material limitations. He also looks at moral-ethical and philosophical consequences of future technologies. Among the themes that Lem discusses in the book, which are gaining importance today, are virtual reality (Lem calls it “phantomatics”), theory of search engines (“ariadnology”, after Ariadne’s thread), technological singularity, molecular nanotechnology (“molectronics”), cognitive enhancement (“cerebromatics”), and artificial intelligence (“intellectronics”).

Early edition of Lem’s book Summa Technologiae

As already noted, Lem’s bibliography includes 18 novels, 14 anthologies of short fiction, and 14 nonfiction works. Readers are encouraged to review many of his works that are available for purchase online and the Amazon website offers a large selection of his works.

Sources: Wikipedia, New York Times, The New Yorker Magazine