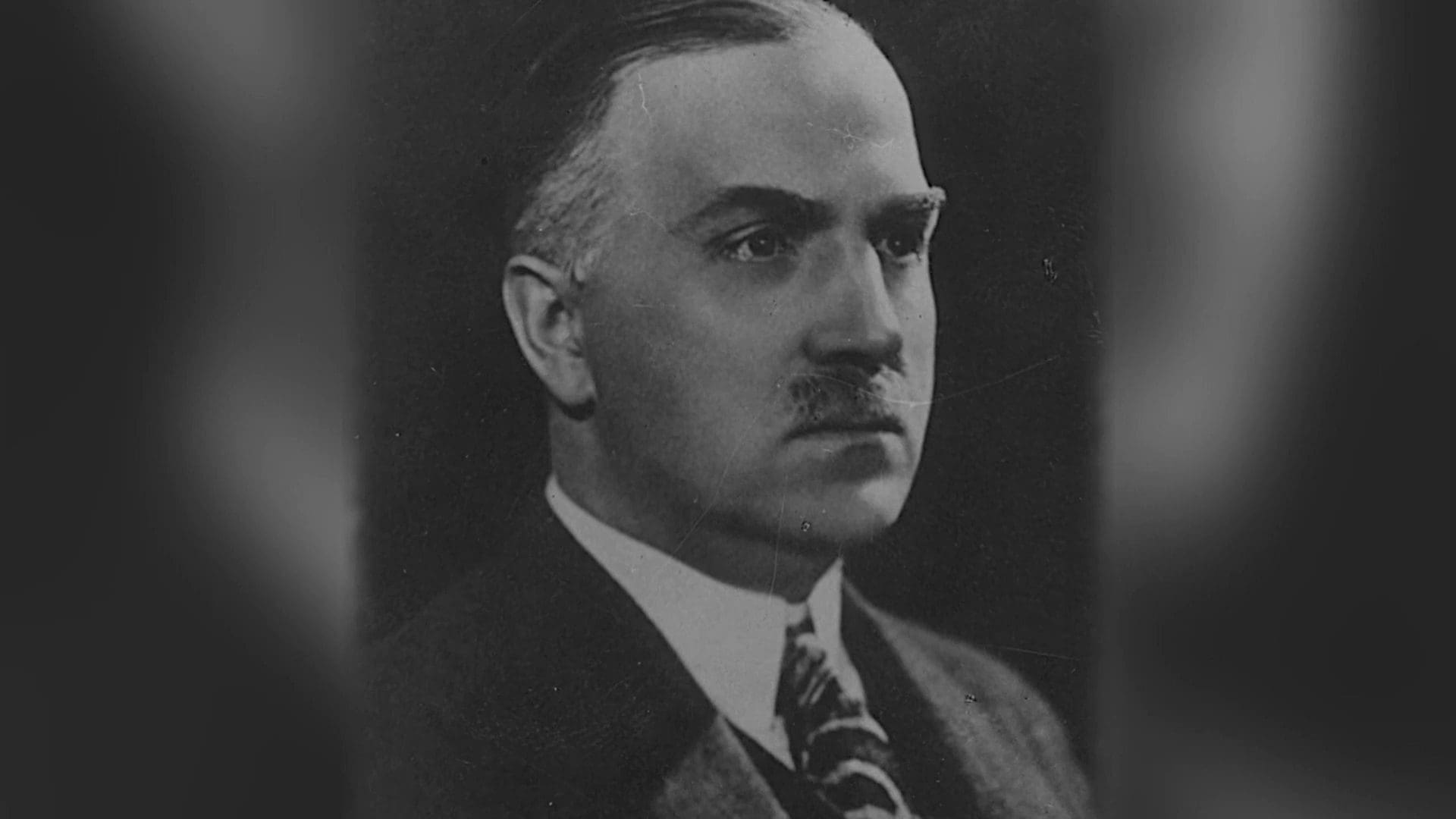

Polish Chemist Creates the Foundation for the Semiconductor Industry

Jan Czochralski 1885 – 1953) invented the Czochralski method, which is the standard method used for growing crystals of silicon and germanium in the production of semiconductor wafers. It is still used in over 90 percent of all electronics in the world that use semiconductors. He was born in the small town of Kcynia (Exin in German) near the Polish city of PoznaÅ„. At the time, this part of Poland was in the Prussian partition, which officially made Czochralski a citizen of Germany.

Czochralski discovered his method in 1916, when he accidentally dipped his pen into a crucible of molten tin rather than his inkwell. He immediately pulled his pen out to discover that a thin thread of solidified metal was hanging from the nib. The nib was replaced by a capillary, and Czochralski verified that the crystallized metal was a single crystal. Czochralski’s experiments produced single crystals a millimeter in diameter and up to 150 centimeters long. In 1948, Americans Gordon K. Teal and J.B. Little from Bell Labs would use the method to grow single germanium crystals, leading to its use in semiconductor production. In addition to the growth of silicon and germanium, the Czochralski method is the leading technique for growing many other crystalline materials, such as high-quality, bulk oxide crystals.

In 1917, Czochralski moved with his family to Frankfurt to found a new large laboratory, one of the bestequipped laboratories then in Germany. There he invented a new metallic alloy called B-metal, which was used to make high-quality elements of bearings for the railway industry. It was cheap, very durable, and, most importantly, did not contain tin, which was expensive and hard to get at the time. By 1928 he was famous and wealthy thanks to his income from this patent.

In 1928 he went with his family to Warsaw at the personal invitation of the President of Poland, Professor Ignacy Mościcki, himself an outstanding chemist. Czochralski said that, because his children were growing up, he wanted to send them to a Polish school so as not to let them become Germanized.

In 1929, Czochralski was appointed Professor at the Faculty of Chemistry of the Warsaw University of Technology and was one of the first to be conferred with the University’s honorary degrees. This was despite not having the formal qualification of the Polish matura, which must be passed in order to apply to a university. At the University, he set up his own Institute of Metallurgy and Metal Science with significant state funding and a large number of staff. By all accounts, his institute was self-contained and seemed to act independently from the rest of the university. Unsurprisingly, this led to jealousy among certain members of the University’s faculty.

Over a period of years from 1930 onwards, new equipment and facilities were added to his institute, some for research into materials for military armaments and some for civilian use. Following Germany’s invasion of Poland, senior German officials visited him, hoping to use his facility for their own purposes. During the German occupation of Warsaw, more restrictions on daily life were imposed on the population; however, Czochralski was able to live largely undisturbed. In April 1945, one month before Germany capitulated to the Allies, the Prosecutor of the Special Criminal Court for the Court of Appeal in Warsaw announced his arrest. This was in accordance with the so-called August Decree, a Decree of the Polish Committee of National Liberation of 31 August 1944, which was the Communist governing authority established by Stalin. Fortunately, the investigation proved that Czochralski’s activity during the occupation did not show collaboration with the Germans and therefore could not be classified as a betrayal of the Polish nation. The trial was a complicated matter, as he constantly maintained his Polish identity despite having been born under Prussian rule. Czochralski was released from prison on 14 August 1945.

The following is information that was later learned about his wartime activities:

- In 1941 the Germans demanded Czochralski’s help to provide materials and equipment for their war effort. However, he did not fulfill them because his facility was overloaded with work.

- There is evidence of his underground activity. Czochralski was given authority to provide employment certificates and he gave many to fictitious employees who were members of the Home Army.

- Together with his daughter, he was able to use his influence with the German authorities to intervene and release certain individuals from concentration and POW camps.

- There is evidence that he manufactured arms for the Home Army, such as grenade shells.

- There is evidence that he sheltered two Jewish women in his home until the Warsaw Uprising in August 1944.

- The German authorities managed to import a vital piece of American equipment with the help of the Swedes. When the apparatus finally arrived, Czochralski used a hammer to smash its essential component, without which it could not operate.

- There is some evidence that Czochralski was instrumental in financially helping a previously owned Jewish business in the Warsaw ghetto.

Czochralski returned to his native town of Kcynia, where he ran a small cosmetics and household chemicals firm until his death in 1953.