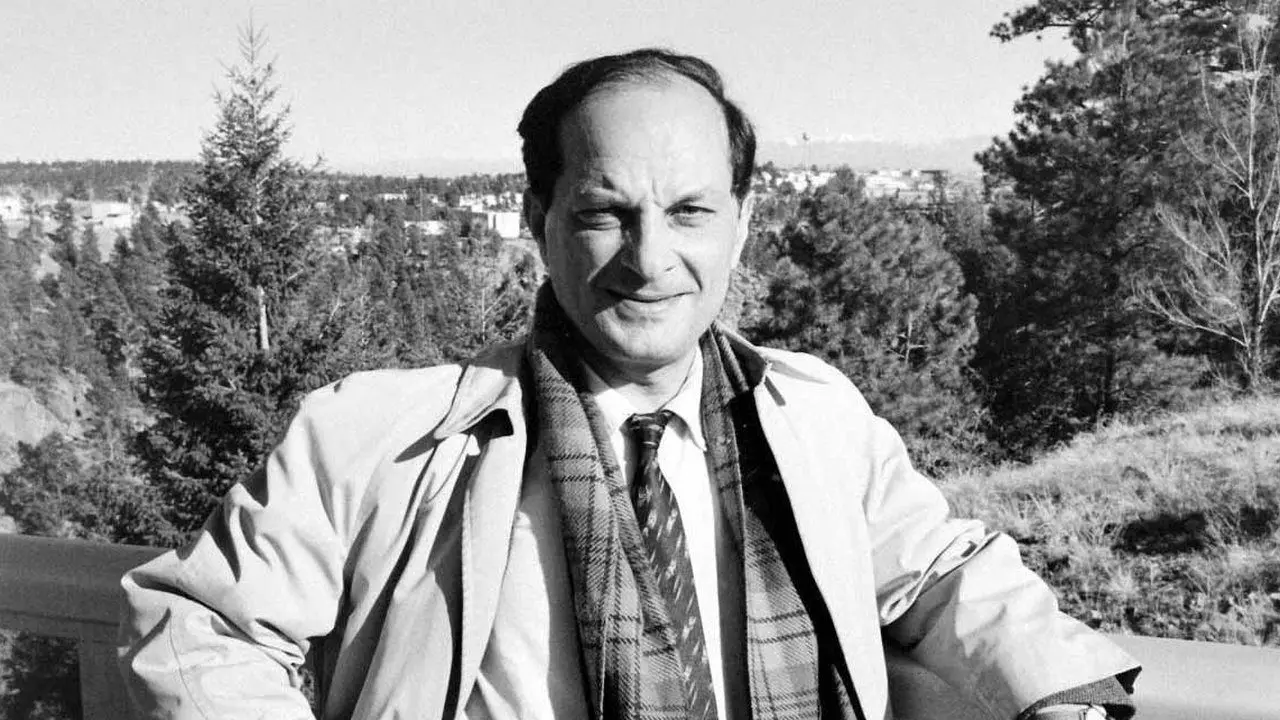

Stanislaw Ulam – Brilliant mathematician with multiple innovations including the design of the H-Bomb

StanisÅ‚aw Ulam (1909 – 1984) was a Polish-Jewish mathematician and nuclear physicist who later became a U.S. citizen. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapons, discovered the concept of the cellular automaton, invented the Monte Carlo method of computation, and theorized nuclear propulsion.

StanisÅ‚aw Ulam (1909 – 1984)

Ulam was born in Lemberg, Galicia, which at the time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1918, when Poland was reestablished as a nation state, the city took its former Polish name of Lwów. He studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute under the supervision of Kazimierz Kuratowski and received his Ph.D. in 1933. Along with StanisÅ‚aw Mazur, Mark Kac, WÅ‚odzimierz Stożek, Kuratowski, and others, Ulam was a member of the Lwów School of Mathematics. Its founders were Hugo Steinhaus and Stefan Banach, who were professors at the Jan Kazimierz University. These mathematicians met for long hours at the Scottish Café, where the problems they discussed were collected in the “Scottish Book” provided by Banach’s wife. Ulam was a major contributor to the book and of the 193 problems recorded, he contributed 40 problems as a single author, another 11 with Banach and Mazur, and an additional 15 with others.

In August 1939, two weeks before Germany invaded Poland, Stanislaw and his 17-year-old brother Adam were put on a ship by their father that was headed for the US. Ulam’s sister Stefania was executed by German camp guards in 1943; his father died in unknown circumstances; and other members of the family also perished.

In 1940, after being recommended by leading American mathematician George Birkhoff, Ulam became an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin. He became a United States citizen in 1941 and in the same year married Françoise Aron, a French exchange student whom he had met earlier at Cambridge. Ulam and his wife had one daughter, Claire. In early 1943, Ulam asked fellow mathematician John von Neumann to find him a war job and later that year he received an invitation to join an unidentified project near Santa Fe, New Mexico. This was Ulam’s introduction to the Manhattan Project, which was the US wartime effort to create the atomic bomb.

Stanislaw and Françoise Ulam

A few weeks after Ulam reached Los Alamos, the project experienced a crisis. It was discovered that plutonium made in reactors would not work in a “gun-type” weapon while uranium would work, and proved to be successful in the” Little Boy” atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. In response, Robert Oppenheimer, Director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, implemented a sweeping reorganization to focus on development of an “implosion-type” weapon. Ulam was assigned to work on the hydrodynamic calculations to predict the behavior of the explosive lenses that were needed by an implosion-type weapon. Despite the primitive facilities available at the time, Ulam and von Neumann carried out numerical computations that led to a satisfactory design.

In 1945, Ulam left Los Alamos to become an associate professor at the University of Southern California. In January 1946, he suffered an acute attack of encephalitis, which put his life in danger but was alleviated by emergency brain surgery. By April, he had recovered enough to attend a secret conference at Los Alamos to discuss thermonuclear weapons. During his participation in the Manhattan Project, Edward Teller’s efforts had been directed toward the development of a “super” weapon based on nuclear fusion rather than a practical fission bomb. After extensive discussion, the conference participants reached a consensus that Edward Teller’s ideas should be further explored and Ulam was hired to lead the theoretical division at Los Alamos. By 1947, Ulam proposed a statistical approach to the problem of neutron diffusion in fissionable material. This statistical approach was called “The Monte Carlo method” and Ulam, together with his colleague Nicholas Metropolis, published the first unclassified paper on it in 1949.

On 29 August 1949, the Soviet Union tested its first fission bomb. This weapon was nearly identical to the “Fat Man” bomb dropped on Nagasaki because its design was based on information provided by spies Klaus Fuchs, Theodore Hall, and David Greenglass. In response, on 31 January 1950, President Harry S. Truman announced a crash program to develop a fusion bomb.

Research on the use of a fission weapon to create a fusion reaction had been ongoing since 1942 but the design was still the one originally proposed by Teller. Because the results of calculations based on Teller’s concept were discouraging, many scientists believed it could not lead to a successful weapon. Ulam and von Neumann then committed to perform new calculations to determine whether Teller’s approach was feasible. To carry out these calculations, von Neumann decided to use electronic computers: ENIAC at Aberdeen, a new computer, MANIAC, at Princeton, and its twin, which was under construction at Los Alamos. Ulam analyzed the chain reaction in deuterium, which was much more complicated than the ones in uranium and plutonium, and he concluded that no self-sustaining chain reaction would take place at the low densities that Teller was considering.

Stanislaw Ulam at MANIC Panel (Credit: American Philosophical Society)

Ulam then proposed another idea in which the mechanical shock of a nuclear explosion would compress the fusion fuel. Teller saw its merit and the two submitted a joint report describing these innovations. A few weeks later, Teller suggested placing a fissile rod or cylinder at the center of the fusion fuel. The detonation of this “spark plug” would help to initiate and enhance the fusion reaction. This design, now called “staged implosion”, became the standard way to build thermonuclear weapons and is called the Teller–Ulam design. With basic fusion reactions confirmed and a feasible design in hand, Los Alamos then tested a thermonuclear device. On 1 November 1952, the first thermonuclear explosion occurred when Ivy Mike was detonated on Eniwetok Atoll. This validated the Teller–Ulam design and stimulated intensive development of practical thermonuclear weapons.

Ivy Mike, the first full test of the Teller–Ulam design on 1 November 1952

Starting in 1955, Ulam and colleague Frederick Reines considered nuclear propulsion of aircraft and rockets. This was considered an attractive possibility because the nuclear energy per unit mass of fuel is a million times greater than that available from chemicals. From 1955 to 1972, their ideas were pursued during Project Rover, which explored the use of nuclear reactors to power rockets.

NASA reference design for the Project Orion spacecraft powered by nuclear propulsion

During his years at Los Alamos, Ulam was a visiting professor at Harvard, MIT, the University of California, and the University of Colorado. In 1967, Ulam was appointed Professor and Chairman of the Department of Mathematics at the University of Colorado. He kept a residence in Santa Fe, which made it convenient to spend summers at Los Alamos as a consultant. He was an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the United States National Academy of Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society.

In Colorado, Ulam’s research interests turned toward biology. In 1968, the University of Colorado School of Medicine appointed Ulam as Professor of Biomathematics and he held this position until his death. When he retired from Colorado in 1975, Ulam began to spend winter semesters at the University of Florida, where he was a graduate research professor. This pattern of spending summers in Colorado and Los Alamos and winters in Florida continued until Ulam died of an apparent heart attack in Santa Fe on 13 May 1984.

Sources: Wikipedia, Institute of National Remembrance website “Giants of Science”, Encyclopedia Britannica